This post was originally published on the HEFCE blog on 19 February 2016 (archived copy).

A key feature of research impact is that it is tangible. Specific people or organisations are affected, and often the impact occurs in specific places. From this stems an important question for research policy: how does the location of the research compare to the location of the impact? Or put another way, if we want to create benefits in a specific place, to what extent should research investment be directed to that location?

This is a live policy and political issue. The Government has initiated a series of Science and Innovation Audits that aim to gather evidence on local strengths. Thinking about place is also important in European research and innovation policy, where Smart Specialisation is a key policy driver.

The impact case studies submitted to REF 2014 provide a useful data source to examine these questions. When we commissioned Digital Science and King’s College London to produce a database of the case studies, they analysed geographical references and were then able to use geo-tagging, with the result that it is possible to search for case studies that describe impact in particular locations.

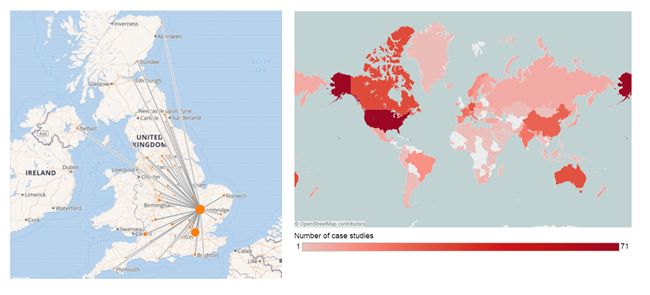

Building on this, we have now developed a visualisation tool that allows the geographical spread of impact to be displayed. This provides a rich and sophisticated picture of the spread of impact from research. Building on previous discussions on this blog on how increased economic productivity depends on the ‘stock’ and ‘flow’ of knowledge and people, the visualisations reveal some aspects of the flow from research to impact.

These visualisations enable a wealth of investigation and analysis, but as you look through the maps these general conclusions become clear:

Impact is not confined to the place where the research carried out.

This conclusion was already clear from the REF impact analysis previously published. The new maps emphasise that the global distribution of research impact applies for most universities. Even the University of Cambridge, which is at the heart of a well-established innovation cluster, has a truly global reach. Across the country, investment in research builds the stock of knowledge which is relatively free to flow to where the knowledge can make impact. And our universities don’t confine their efforts solely to their locality. Rather they seek to maximise impact wherever it is best delivered.

Research across the UK leads to impact in London.

Despite the broad spread of impact from research, London is a dominant location for impact within the UK; almost every university has at least one case study with a mention of the capital. This reflects the dominance of London in economic, political and cultural terms, and provides further evidence that knowledge flows to where it can be most effectively used. It may be a matter of debate whether the dominance of the capital is positive or not, but this observation suggests that regional targeting of research investment may not be an especially effective mechanism for changing the pattern of economic activity.

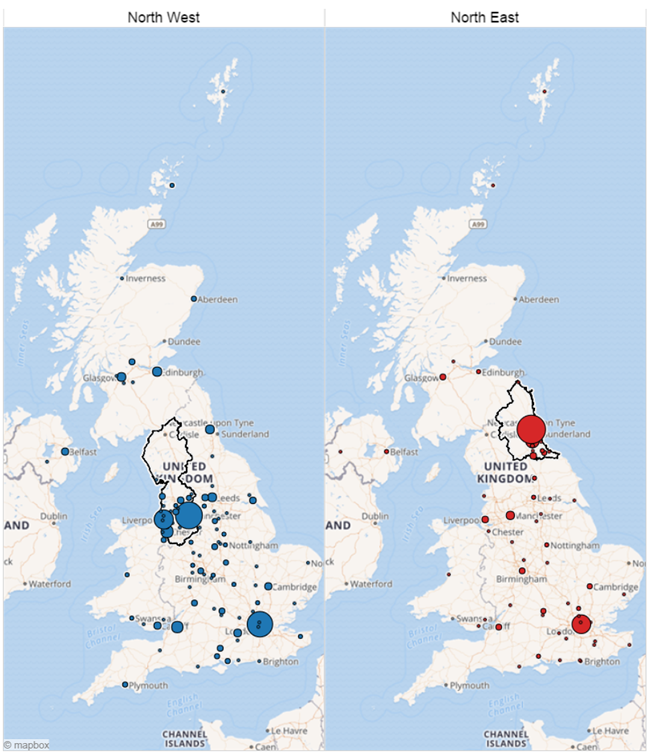

There is some regional focus of impact.

Although research impact is global, most universities show some propensity to support impact near to their location. This is most evident looking at the regional clustering of impact. For most regions a significant proportion of impact from research is delivered within the region. This reflects that, while knowledge flows relatively easily, other aspects of the ‘stock’ that derives from research investment is more tied to a specific place. Expertise and know-how of skilled people are more localised, and impact that derives from the collaboration and co-creation will be limited in the distances that can be cost-effectively covered.

Some regions are more locally focused in terms of impact than others.

While these maps haven’t been analysed statistically, there does seem to be a difference in the extent to which impact is regionally focused. Some regions are more inward-looking than others. Compare, for example, the maps for the North East and North West above. There are positive and negative aspects to a more local focus. The benefits of research are being delivered close to where the research is being carried out, but there may be missed opportunities where even greater impact could be generated at more distant locations. There is also evidence that more outwardly focusing regions tend, somewhat paradoxically, to be the most prosperous.

This all raises interesting questions for regional research policy. For decades the UK’s approach to research investment has been to support high quality research, wherever it is found, and there is nothing in this analysis that suggests changing that. The delivery of impact from research is a complex interplay between supply, demand and co-creation, where place is undoubtedly a driver without ever being the primary driver. These new maps give us a new opportunity to explore these interactions in some detail. But there is a generic conclusion in my view: Each university is unique with its own mix of research strengths and local conditions, and there is huge strength in this diversity. As ever, one size won’t fit all.