In November I attended a 'Séance de Réflexion' organised by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) on the topic of research excellence and how to measure it. This post is a blend of the argument that I made in my presentation, and the wider discussion at the event.

The concept of excellence is central to discussions about research, whether those discussions are held between policy-makers, funders or researchers themselves. While the word 'excellence' may not always be present, the idea of relative merits and hierarchy are deeply embedded into the whole notion of research. Whether it is 'first' or 'better', research moves on from, and so supercedes or enhances what has gone before.

It is important to stress that notions of excellence are embedded within the community of researchers themselves, as well as in the wider policy and funding environment within which they operate. Research has always embraced prizes and other honours, such as fellowships of national academies, as mechanisms to recognise the best and most important contributons. For example, the UK Royal Society awards fellowships (a maximum of 52 each year) to those who are "elected for life through a peer review process on the basis of excellence in science" (my emphasis). These inherent hierarchies aren't limited to the level of individual, but also are applied to research outputs or articles. This happens through informal networks, but also more formally through structures such as the Faculty of 1000, an online platform where "Over 8000 experts from across the globe pick out what they think is the most exciting and important research emerging today".

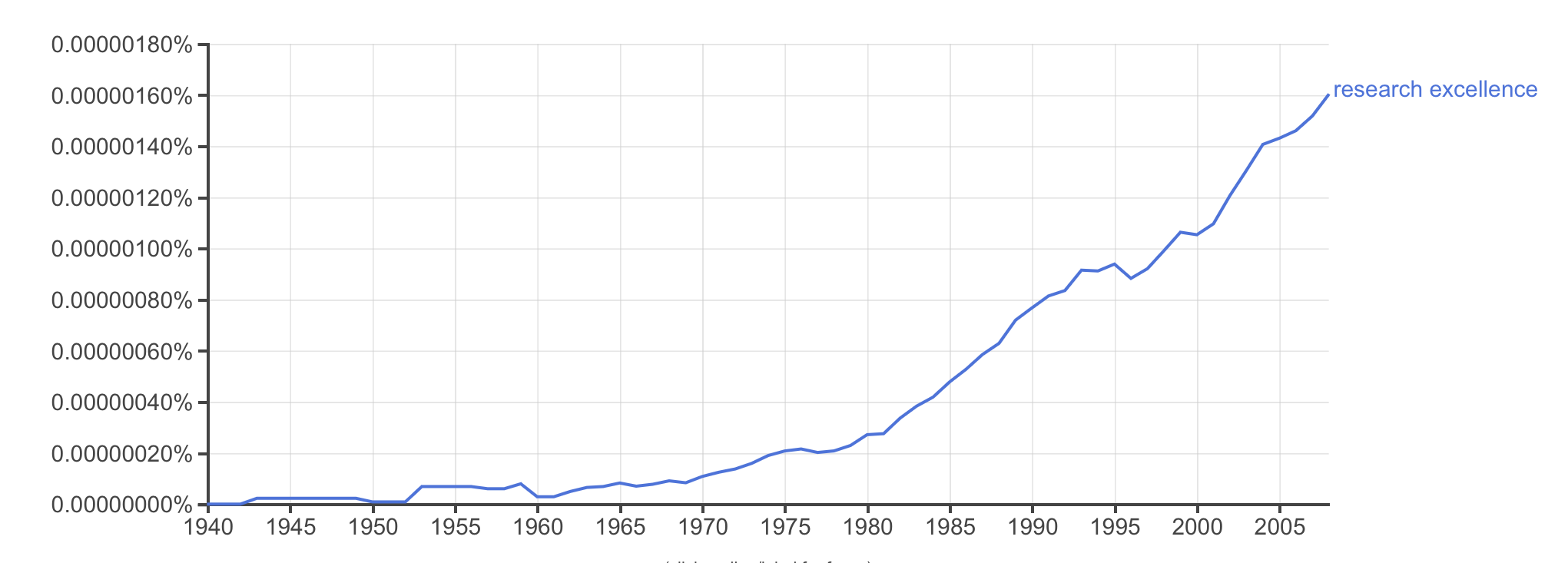

Although the idea, if not always the word excellence is commonplace, the word has indeed become more prominent in the lexicon of research funders and policy-makers, and more broadly as the Google ngram chart below illustrates. The law[pdf] establishing the Swiss National Science Foundation requires that the Foundation supports, among other things, "excellent research projects". While the legislation in the UK doesn't mention excellence, it is a thread that runs through the policy of public funding, not least in the national research evaluation, the Research Excellence Framework(emphasis added…). As well as researcher-led ideas of excellence, there is also now Excellence, capitalised, within the policy world.

In the course of the discussions at the SNSF meeting it became apparent to me that, as well as a divergence in the origins and use of excellence between researchers, and funders and policy-makers, there is also a fundamental difference in the way the term is used. For many, excellence goes hand-in-hand with ideas of scarcity and relative performance. For example, in rankings of universities or the category of the most highly cited articles limits are placed on the number of excellent things. In the same vein there is an annual limit on the fellowships awarded by the Royal Soceity mentioned above. Put another way, this way of thinking implies that, however good overall or average performance might be, only a limited number of people or articles or projects can be considered excellent. There is an alternative way to frame excellence - as an absolute standard (or set of standards). In this framing there is no reason, in principle, why all research or no research in a given context can meet the standards of excellence.

Of course in the context of funding decisions, there is an in-built notion of scarcity with a fixed amount of funding to be distributed. Absolute standards of excellence may not help make decisions if everything is rated as excellent. In this case the identification of applications at the top of the rank order is needed, but we need to be careful about ascribing this selection to the identification of high absolute performance as it may only reflect relative performance.

As well as debates about whether excellence is relative or absolute, the criteria which underpin the attribution of the title are also the subject of discussion and critique. One of the most interesting analyses of the concept is the provacatively titled paper Excellence R Us by Moore et al.1. In this paper, the authors argue that research excellence is an ill-defined concept, and especially that it is difficult to operationalise across disciplinary boundaries. They also sugguest that often the criteria for excellence are not made sufficiently explicit or transparent, and that often inappropriate proxies are used, especially for the quantitative comparison of excellence. Finally, they argue that excellence in research tends to be viewed along only a single dimension, with a strong focus on research outputs and perceptions of their quality.

Where my view differs from Moore et al. is in situating the source of these problematic aspects of excellence. They focus on factors external to the research system - policy and funding systems, university management, and wider factors like international university rankings. While these no doubt play their part, there are also strong drivers towards problematic notions of excellence from within the research system and researchers themselves.

As an example, we only need to look as far as the previosuly mentioned election to the fellowship of the UK's Royal Society. In the publicly available information there is only one, rather general, and potentially subjective criterion:

"Candidates must have made 'a substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematics, engineering science and medical science'"[Emphasis added]

In terms of the evidence provided to support the consideration of a candidate this is limited to "a full curriculum vitae, details of their research achievements, a list of all their scientific publications and a copy of their 20 best scientific papers". This implies that a great emphasis is placed on publications, and suggests that there is a volume threshold in terms of the number of publications.

The relatively vague criterion, and implied unidimensional approach to excellence are coupled with a closed and arcane nomination and election process. Even the membership of 10 'Sectional Committees' that filter potential candidates does not appear to be published. No doubt some researchers are aware of the memberships of these committees, but this information is not made available to all in an equitable fashion.

External to the research system, uni-dimensional quantitative measures of excellence that are based on poor proxies are also commonly found. For example, the research element of the Times Higher Education (THE) world university rankings depends to a great extent on a citation-based measure. While this proxy does take into account disciplinary differences in citation practices by using a field-normalised approach, there are many, many other limitations with the use of citations. The approach also ignores other factors or criteria that could considered elements of excellence in research2.

There are many other example of excellence becoming collapsed to single-dimensional and inappropriate proxies. Notwithstanding considerable efforts, journal based metrics are still routinely used inappropriately in judgements of research outputs, or even individual performance, as evidenced by analysis of promotion and tenure requirements. Article-level citation-based metrics, while preferable to journal-level metrics are also widely and uncritically used. There is evidence that citation rates are dependent on the location of publication as well as features of the article itself, for example. As well as the inherent problems with citation measures, they also encourage the restriction of excellence to a single dimension.

As I have argued previously, a central limitation to the way that excellence is used within the discussion of research is its consideration against only a single dimension of activity. Rather than abandoning the idea of excellence as a driving force with research policy, we need to redefine the idea as reflecting the multidimensional reality of research excellence. Alongside careful definition of criteria and caution about the use of quantitative proxies, we need to define excellence in a way that ensures proper recognition and reward, and provides the incentives for a research system to serve the needs of society.

The evolution of the UK's Research Excellence Framework (REF) represents a real-world attempt to implement a more plural and inclusive notion of excellence. While no doubt there are areas for improvement, and some features of the system are inevitably driven by the pragmatic needs of policy, the framework addresses some of the challenges associated with excellence.

Transparent criteria for excellence, defined by identified expert panels of researchers has been a feature of the UK's research assessment system over much of its 30-year history. More recently, a real broadening of the dimensions of excellence has occurred with the inclusion of an element related to the societal impact of research, alongside an assessment of academic impact based on research outputs. While not without its challenges for assessment, the impact element is an important balance against the dominance of academic research outputs, and the importance of impact has been increased for the current iteration of the exercise.

As well as the outcome-related areas of research outputs and impact in REF, a third element, research environment, also features, and brings an important focus on both features of the research process and some element of strategy and forward trajectory for research units. There is increasing focus on the elements of process covered within the research environment element in policy debates. Questions about how to support properly the careers of researchers, improve the representativeness of the research workforce, challenges for research integrity and reproducibility, and the enhancement of the openness of the research system are all now regularly debated. More broadly, it is becoming universally recognised that the culture of research needs to be improved.

Responding to evolving policy agendas is likely to feature significantly in thinking about the future of research assessment in the UK after the present exercise is completed. The balance between the different dimensions of excellence will be an important part of this consideration. Given the priority of issues relating to research culture, we will need to consider carefully how to incorporate them into the environment element, and give them appropriate weighting.

The idea of excellence has been and will continue to be central to research policy globally. Even with the challenges associated with excellence it is hard to argue against excellence with senior policy-makers or politicians. Instead, we need to resist narrow, opaque and uni-dimensional approaches to excellence that are based on poor proxies. Developing these broader more nuanced views of excellence is itself a new challenge for research policy. But perhaps the bigger challenge is communicating broader ideas of excellence. Across the globe, and perhaps especially in the developing research nations of the South, there is a risk that an overly constrained view of excellence is adopted. Now is the time to over-turn this view and replace it with a more appropriate and balanced idea of research excellence.

-

The full is reference is: Moore, S., Neylon, C., Eve, M.P., O’Donnell, D.P., & Pattinson, D. (2017). “Excellence R Us”: university research and the fetishisation of excellence. Palgrave Communications, 3, 16105. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.105 ↩

-

The research element of the THE ranking also includes research funding (an input measure) and productivity (measures as the number of jounral articles per academic), and also research reputation. The latter is measured through a survey, although it is not clear how or whether excellence within the survey is based on specific and explicit criteria. THE also publish a separate ranking based on impact (defined with reference to the UN sustainable development goals) that also has a research element, again focussed on jounral articles and citation-based indicators. ↩