Much has already been writen about the new world that will emerge following the acute phase of the coronavirus pandemic. One idea that crops up repeatedly is the notion that, as well as presenting many challenges, the current circumstances present an opportunity to rethink and reset. We don't need to go back to what came before and that is a positive from the crisis. This was captured especially eloquently by Arundhati Roy who described the pandemic as portal to a new world which "we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world".

This implies making some choices to do things differently. Writing in the Future Crunch newsletter, Gus Hervey argues for an approach to rethink our economic goals and structures. The piece draws on the work of two economists - Mariana Mazzucato and Kate Raworth. Mazzucato has argued in a number of books, most notably The Entrepreneurial State, that there is a need to recognise the central role of the state in innovation. This book and its arguments has received considerable attention in the innovation and research policy communities. I was personally much less familiar with Raworth's work, and while I had heard of her book, Doughnut Economics, I hadn't read it. Having read the book, I find that the arguments are compelling. As well as providing a valuable impetus to thinking differently about the future economy, the ideas in Doughnut Economics provides a useful framework for thinking about research strategy and direction.

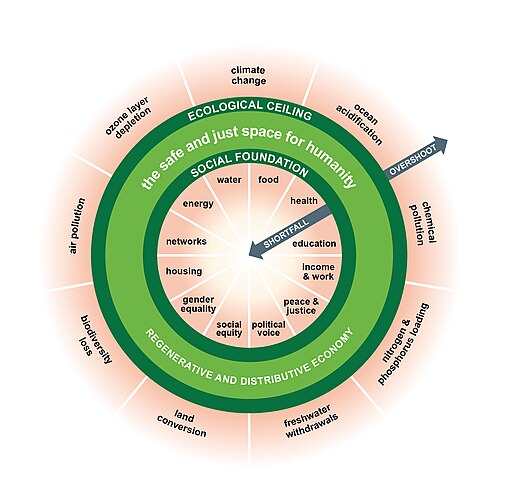

The central idea in Doughnut Economics is that we need to replace GDP growth as the principal goal of economic and public policy. As well as being too narrow a measure1, Raworth argues that the focus on growth inevitably creates unequal societies and leads to environmental degradation. Instead Raworth introduces the idea of target to maintain the world in a 'safe zone' of her 'doughnut'. The minimum requirement is that everyone on the planet is able to reach a set of standards, the 'social foundation', defined by the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The maximum corresponds to a set of clearly defined limits of the earth's environmental system, the 'ecological ceiling'.

Currently, we are definitely outside of the 'safe zone', with huge numbers of people globally not reaching the social foundation, while at the same time significantly exceeding the ecological ceiling. Having set this goal, Raworth goes on to explain a range of changes needed to the world's economic system that will contribute to achieving the goal. Some of these are radical, some surprisingly simple, but, overall, the book presents a compelling agenda for a new future.

While there are many actions that are needed to stimulate progress into the safe zone, how could we orient the research system more with this vision of the future? I think there are three ways that research strategy and policy could respond.

Fund more research into developing the ideas behind Doughnut Economics. Although the book contains evidence to support the alternative economic model it espouses, in order to convince decision-makers, and to refocus away from GDP growth, further research is needed. I was especially struck by the chapter that discusses the application of a systems approach, and complexity theory to problems of the economy and society. This seems a powerful approach, and instrumental in demonstrating the overly simple view of much policy making, and so is worthy of more research effort.

Focus research on the safe zone. If my first point is focussed on a very specific area of research, the second is about a broad research agenda. If we are to get into the safe zone of the doughnut, then there is a major research effort needed against each aspect of both the social foundation and the ecological ceiling. We need to focus effort on these areas and only support research that is delivering against the lower and upper limits. This does not necessarily imply that all research should be aimed at immediate problem solving, as there are many questions that require better fundamental understanding. But if we are to get to the safe zone, there is a need to incentivise and focus on research that has a plausible pathway to get there. Not everything will achieve its expected outcome, but the idea of the doughnut gives a framework within which to consider research impact from a more normative perspective. The type of research impact matters and impact that only generates narrow economic growth at the expense of the social foundation or the ecological ceiling should not be a priority for public investment.

Consider adopting a 'doughnut' approach to research policy. There is also the potential to explore how the ideas of Doughnut Economics could be applied to policy for research, and some of these ideas have already attracted interest. For some time, researchers, funders and others have been promoting open research and the idea of constructing a global knowledge commons, an important idea advocated by Raworth. A more radical avenue to explore would be the application of a more redistributive approach to research funding. There are already advocates for alternatives to a competitive approach to funding distribution, including using basic research income, peer allocation mechanisms, and random allocations. Maybe now is the right moment to give these alternatives some serious consideration. Finally, one of the key notions that Raworth puts forward in the book is to treat the economy holistically, and recognise that it is a complex system. This is also true of the research system, and, while the language of systems thinking is often used in the context of research, a systems approach is less often used in practice. Considering how to make research policy in a whole system context is an interesting challenge that merits further exploration.

-

Mazzucato's Value of Everything is an excellent longer review of this question. ↩