Towards the end of 2018 an important new report was published by RAND Europe. Commissioned by the UK's National Academies, the report is titled Evidence synthesis on measuring the distribution of benefits of research and innovation, and provides an overview of the evidence concerning a central question for research policy: what are the benefits of investment in research and innovation?

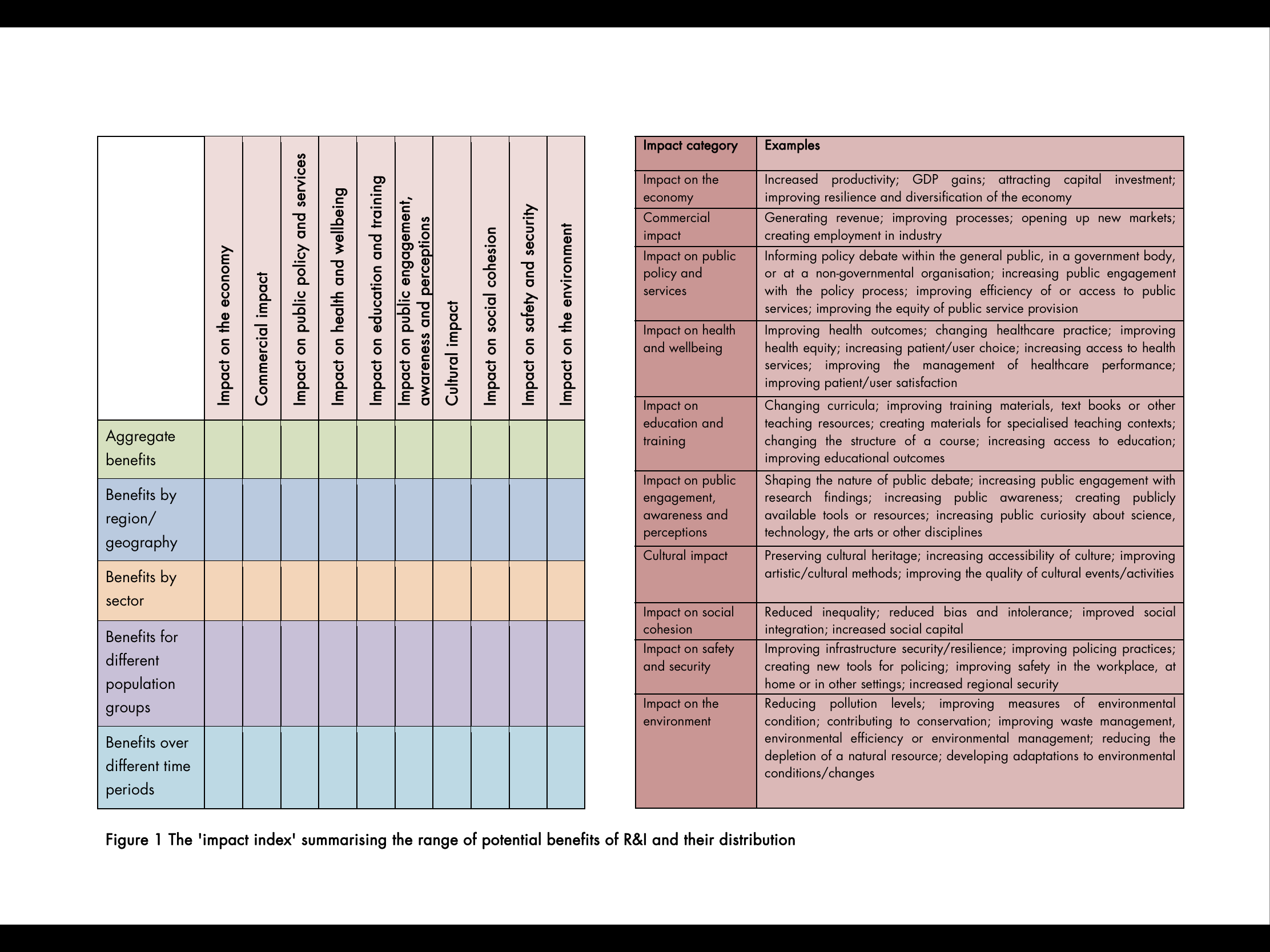

As well as being an excellent summary of current evidence, the report also takes the area forward significantly, through a conceptual framework for research impact (see digram below), and an evidence assessment and gap analysis against the framework.

The framework is really valuable, because it attempts to be comprehensive, and provides a clear way of articulating the full range of benefits, and the different lenses through which those benefits can be viewed. Based on the framework, the gap analysis is sobering, if not unsurprising. The available evidence is strongly skewed to the top left of the impact matrix, focussing primarily on the aggregate analysis of economic benefit, and commercial impact. This means that we are certainly dramatically underestimating research benefits.

It is also striking that where evidence does exist of benefits beyond the economic and commercial, there is a very strong reliance on case studies, with their inherent limitations. From a personal perspective, it was pleasing to see the importance of the REF 2014 impact case study database acknowledged, but clearly this data source needs to be supplemented with other sources and analyses to get a better and more systematic understanding of the full range of benefits.

The report emphasises the potential value of extending the integration and use of existing data on the benefits of research, a recommendation I wholeheartedly support. We need to make more data about research impact available in forms that allow it to be easily linked to other data sources. For example, while Gateway to Research surfaces much of the outcomes data collected in the ResearchFish system for Research Council grants, it is not always straightforward to use. And the wealth of data that other funders collect is not even made available publicly in a complete or linkable format. For example, in 2017 the Association of Medical Research Charities published an impressive report about the impact of the research their members fund, but none of the underlying data can be accessed, interrogated independently or linked to other data sources.

In providing a framework for discussion of evidence needs, the RAND publication makes an important contribution. As we move into a no doubt challenging discussion about future spending on research in the UK, the report provides a useful summary of the available evidence, but also points to the future research agenda needed to fills the gaps.