Earlier this month I had a post on the HEFCE blog related to the current recruitment of panel members for the REF. Arguing for the importance of international members on the panels, I suggested that the very idea of comparing the research performance of different nations is no longer sensible. In this post I want to expand on this idea.

The notion that the research of the UK and other developed nations is increasingly international is not a new one. Writing in 2013 Jonathan Adams coined the term the 'fourth age' of research to reflect its internationalisation. He and Karen Gurney further developed the idea in a 2016 report. The evidence to support the idea continues to build, and I think it questions whether the construct 'national research' has meaning, at least for well-integrated nations like the UK.

Focussing on the UK, four pieces of evidence suggest that it is difficult to speak about national research.

1. The volume of international collaborative work. Recent analysis by Elsevier for the UK Government, shows that the proportion of UK articles with an international co-author has been steadily rising for a number of years. In the most recent year of analysis, more than half of the journal articles with a UK-resident author also have a non-UK-resident author.

2. The role of international collaborative work. This report also provides information on the number of citations that articles with or without international co-authors achieve. The numbers aren't provided directly, but there is enough information to estimate the field weighted citation impact (FWCI) of articles with and without international co-authors. Overall, articles with UK-resident authors are cited 1.57 times the world average. However, the FWCI of articles with only UK-resident authors is 1.18, and those with at least one non-UK-resident author is 1.97. Domestic output is only a little above world average, whereas work involving international collaborators is almost double the world average. When we talk about the UK's excellent research performance we are actually referring to excellence that is acheived in collaboration.

As an aside, this observation is also important in interpreting analysis like the Elsevier work. The higher citation rates of internationally colaborative work is common to other nations in addition to the UK. And the Elsevier work uses a whole-article counting approach which means that many highly cited articles are counted in the performance of more than one nation.

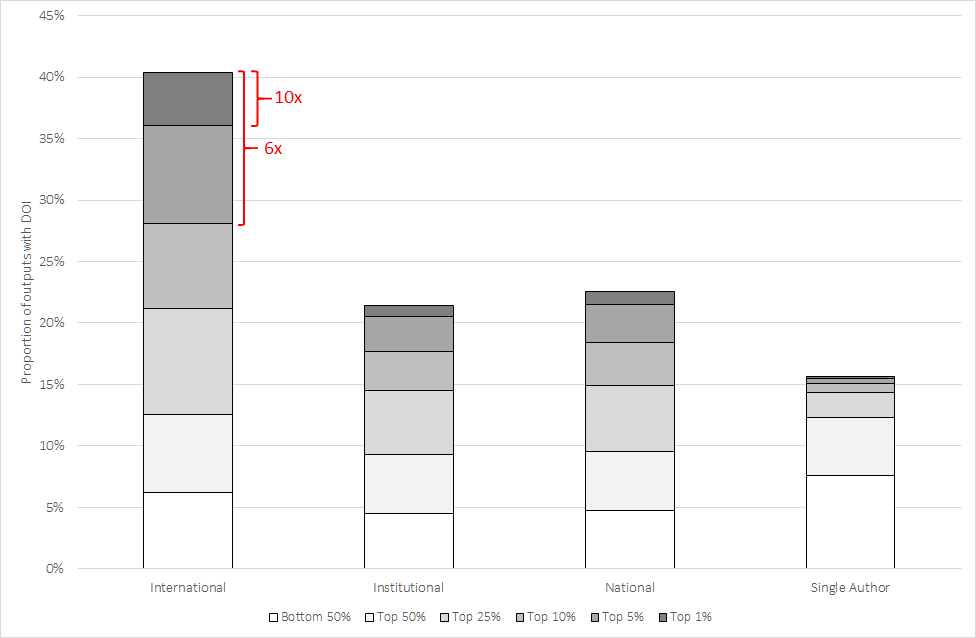

As well as in analysis of total national article output, the contribution of international collaboration can also be seen in the journal article outputs submitted for assessment in the Research Excellence Framework (REF). Some 40% of the articles submitted in 2014 have an international co-author, and, as the chart below illustrates, these are more highly cited. Articles from the global top 1% in terms of citations are 10x over-represented in the internationally co-authored articles, those from the top 5% are 6-fold over-represented.

3. The international nature of the research workforce. So, the bibliometric evidence suggests that a lot of research with UK-resident authors also has non-UK-resident authors, but in addition there is a significant international presence within the group of UK-resident authors. Analysis by the Royal Society reveals that 28% of UK academic staff are not UK nationals. And when the data on PhD students was examined, around half are not UK nationals.

4. The international nature of research funding. Finally, funding from outside the UK is important within the UK research system. According to data from the Office for National Statistics, 17% of the UK's funding from research came from overseas sources in 2015, and this proportion has been relatively constant for the preceding decade.

Taking this evidence together it is hard to delineate what is meant by 'UK research'. While the UK does appear to be very integrated into global research, it is by no means unique, and evidence suggests that international integration and high performance in research go hand-in-hand.

The international nature of research has important implications for domestic research policy. It places considerations of international strategy at the heart, not the periphery of policy thinking, with steps to reduce or eliminate barriers to collaboration being essential. But most importantly, internationalisation calls for a very different mindset, where the outputs of research investment are not viewed as a national asset, but part of a global knowledge commons. This in turn means we need to challenge the simplistic links between research investment and national benefits, be they economic or relating to broader societal impact. While it is perfectly reasonable to look for national benefit from national investment in research, the benefits come from being part of, and having access to the global knowledge commons. In this way of thinking, national investment in research is about contributing to global knowledge on the one hand, accepting that other nations may benefit from that contribution. On the other hand, national investment is needed to give the nation the absorptive capacity to make the most of the insights generating by global research.

Most of all, the international nature of research should take us away from narratives of national competition in research, and remind us that diverse partnerships in research bring mutual benefits to all involved.