Yesterday I spoke at the University Press Redux conference University Press Redux conference in Liverpool on the role of policy in shaping the academic book of the future. This post is a summary of the argument of my talk.

Henry Ford, speaking about the development of the model-T Ford, famously said “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses”. In one sentence, he summarised the challenges associated with innovation, and these challenges apply no less to scholarly communication than they do to transport. Take a long hard look at the response of the world of books to the digital age, and you might consider that current e-readers do indeed represent the equivalent of ‘faster horses’.

It’s not that the digital and connected world doesn’t offer considerable potential for innovation for the book, in general, or the academic book, in particular.

The book is an essentially linear format, where the reader is locked into the path chosen by the writer. It doesn’t have to be like this, and in the academic context linking together ideas in a different order, or even blending the thinking of multiple authors, has real potential to advance scholarship. Innovation like this is already happening in the world of fiction: for example, Arcadia by Iain Pears is a novel available only in digital formats, that allow the reader to navigate their own route through the narrative.

Digital formats also offer the possibility to make, re-use and share annotations. Alongside the ability to search text, annotation is a key feature of digital content that is available even if that content is presented in a traditional book format. At the moment much of this potential is limited by a lack of combining annotations in standard format from different sources. Looking at my own reading habits, I make notes and highlights in different places: on a Kindle, in various different pdf readers, or in the ‘read-later’ service Instapaper. Bringing together these annotations into a modern-day commmonplace book is much harder than it should be. There is hope in the shape of the service hypothes.is which provides a unified annotation (and sharing) function across a range of content, with recent progress being made with partnerships with several scholarly publishers.

Finally, there is the potential for the digital ‘book’ to expand into content beyond the printed word. Look, for example, at Alice in Dataland. In this work, the author, Anastasia Salter, presents the outputs of scholarship in a range of interconnected formats, including, but not limited to text.

While there is much potential for innovation, the uptake seems slow. There is lock-in, with the conventional book occupying a place within the academy that is not unlike the position of the qwerty layout on our keyboards. Even when we see the benefits of innovation, the change in process and practice is real barrier.

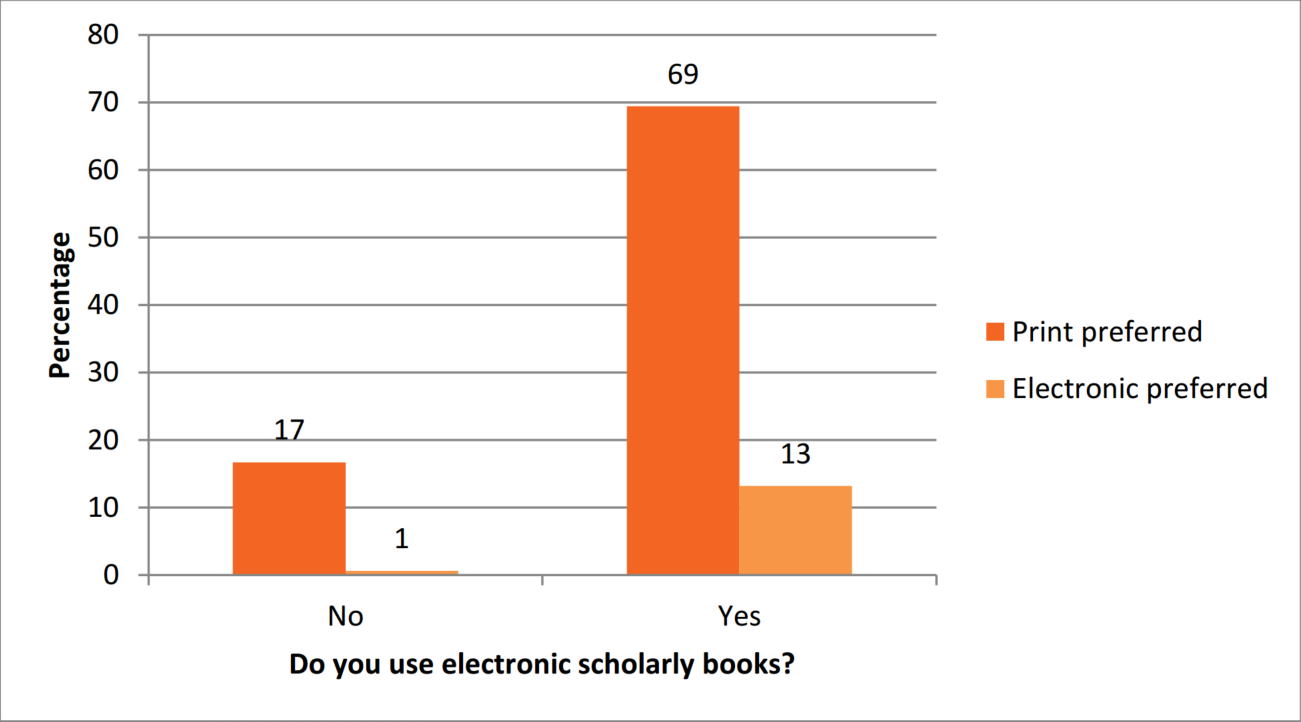

And, like Henry Ford’s potential customers, there is conservatism in academic community, both the producers and users of the academic book. A recent survey, carried out as part of the OAPENUK project, found that even among researchers who use electronic versions of scholarly works, there was a strong preference for print.

There is a strong perception in the academy that the book can’t be improved, exemplified by this quote from the late Umberto Eco:

“The book has been thoroughly tested, and it’s very hard to see how it could be improved on for its current purposes. Perhaps it will evolve in terms of components; perhaps the pages will no longer be made of paper. But it will still be the same thing.”

So, if there are benefits from potential innovation and development of the academic book, but there are barriers to progress, what can and should be done to the research policy environment to encourage change? The general response of policy-makers in response to this question is to focus on making space for innovation; a focus on being permissive and removing barriers. An example, would be the guidelines for research assessment, making it clear that innovation in research output is acceptable. For REF2014, the guidelines said:

“An underpinning principle of the REF is that all forms of research output will be assessed on a fair and equal basis. Subpanels will not regard any particular form of output as of greater or lesser quality than another per se.”

Even though similar statements have been made for past exercises, the outputs submitted for assessment remain resolutely traditional. Important as it is, simply making space for innovation may not be enough.

Maybe we need to focus more on making space, putting the emphasis on active creation of innovative practice. Setting aside some funding for supporting innovation is one option, although there is always the risk that direct funding just stimulates innovation for the sake of winning funding, rather than truly enhancing academic practice. But perhaps more important is to find ways of showcasing and celebrating diverse and innovative scholarly communication. The Academic Book of the Future project is doing this, but I wonder whether a national competition, we an emphasis on both innovation and leading scholarship might also make a difference.

There is, of course, a role for publishers in supporting innovative practice. The University Press is particularly well placed to do so, in my view. Positioned close to the academy, University Presses have direct access to leading scholarship and should be well placed to both identify innovation where it appears, and also to suggest innovative options to authors where it could make a real difference. University Presses should also be able to access research in technology development, looking for options where new technology can enhance scholarly communication. Finally, if Universities themselves are willing to see Presses as places of innovation, there is the potential for business models that allow the risk-taking that is needed.